Sweet Tooth: The Effect of Sugar on our Oral Health

Guest Blog by Simryn Johal, Action on Sugar Volunteer

Summer is here, (although sometimes hard to believe!) and so is the ice-cream. Unfortunately, our teeth are not as happy to see the sweet stuff.

Recently, I had the eye-opening experience of treating young children with shockingly large cavities in their teeth. In some cases, the decay was so extensive that I would have to refer them to hospital to have teeth extracted. This kind of dental trauma can have lasting effects on children and cause dental phobia in adulthood.

Untreated dental caries can lead to extremely distressing consequences such as pain, trouble eating and sleeping, and even risk of dental sepsis1. It is shocking that tooth decay is preventable, and yet it is the number one reason for hospital admissions in 5-9 year olds2.

In 2019, Public Health England reported that nearly 25 percent of five-year olds had dental decay when they started school, with over 25,000 hospital admissions for extractions. That has resulted in 60,000 days of school absences in just one year2.

As many parents will know far too well, toothbrushing-time can be a daily battle in the household, with kids less likely to brush their teeth at all let alone floss. On top of this, many children will find it difficult to understand the effect sugar has on their teeth, and why they might need to cut down on the very tempting treats. As the protective layer (enamel) of baby teeth is thinner than the enamel of adult teeth, it is important to instil good habits from a young age.3

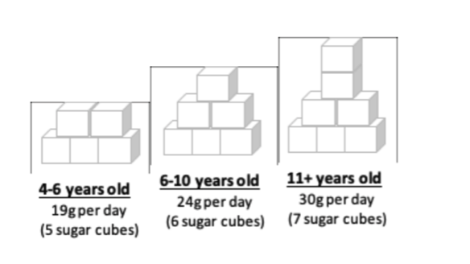

Children are consuming nearly triple the recommended daily amount of free sugars. Free sugars are defined as ‘all sugars added by the manufacturer plus those naturally present in honey, syrups and unsweetened fruit juices’.4

Public Health England (2015)4 advise that the recommended intake of free sugars is no more than:

So what exactly happens when we eat sugar?

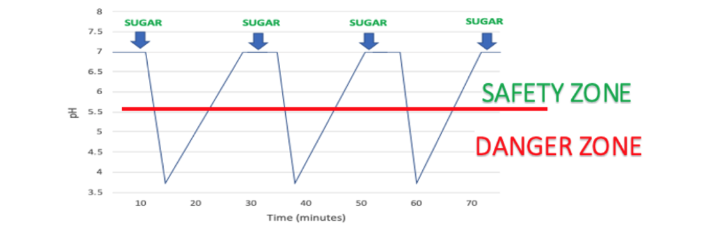

We have all heard that “sugar rots your teeth”, but have you ever wondered what exactly happens? Dentists often describe this as ‘the constant battle’, and it’s shown in an illustration called Stephens Curve5:

Every day, there is a battle in your mouth between good and bad bacteria.

Sugar consumption creates an ideal environment for bad bacteria to thrive. The bacteria feed off sugar, producing acid which can damage the outer layer of your tooth (the enamel), in a dynamic process called demineralisation. This is followed by a gradual recovery where good bacteria thrive, usually over a period of 30 to 60 minutes.

Eating too much sugar, too frequently, means your teeth are exposed to bad bacteria, the acid produced as a by-product leads to the formation of cavities. Untreated cavities can grow, trapping more bacteria and can lead to pain, infection and sometimes removal of the tooth6.

So – try to consume sugar in one single sitting at a meal time, rather than exposing your teeth to numerous small attacks throughout the day.

Spotting ‘hidden’ sugars

Even those of us without a sweet tooth may be eating more than we realise because so many processed food and drink (cereals, pasta, low fat and ‘diet’ foods) contain added sugars to help improve their taste & to add bulk in the place of fat. Look in the ingredients list for anything ending in ‘ose’ (glucose, sucrose, fructose) – these are all forms of sugar, as are honey, agave and syrups. The higher up the ingredients list, the more sugar the product contains.

What about fruit?

Natural sugars found in whole fruits and vegetables have health benefits and should not be avoided. The issue occurs when fruits are blended - this process releases sugars so that they are instantly available for bacteria to feed on. These include the ‘naturally occurring sugars’ in healthy fruit snacks or the ‘no added sugars’ in your healthy fruit yogurts. Once they are processed and pureed, they react in the same way as other free sugars. So, it’s best to opt for fruit in its natural form rather than blitzing or buying fruit juices.

Is there anything we can do to fight it?

Luckily it is not all doom and gloom; the good news is that damage is constantly being reversed, and there are ways we can encourage our mouth back into remineralisation (the ‘safety zone’).

TOP TIPS

1. Brush your teeth twice a day

Though you cannot ‘out-brush’ a bad diet - brushing for two minutes, twice a day certainly helps to keep the bacteria at bay. Studies have shown that the average time people brush for is just 45 seconds7. An electric toothbrush with a two-minute timer can help to ensure you’re brushing for the correct amount of time!

Fluoride in your toothpaste helps to repair weakened enamel.

· Children under 3 years should use a smear of toothpaste containing atleast 1,000 parts per million (ppm) of fluoride8.

· Children aged 3-6 years should use a pea-sized amount of toothpaste containing more than 1,000ppm fluoride8.

· Ages 7 and above can use a family fluoride toothpaste (1,350-1,500ppm fluoride)8.

Once you have finished brushing, avoid rinsing with water. Just spit and allow the toothpaste residue to sit.

2. Make regular trips to the dentist

Regular trips can allow your dentist to spot decay early, and help reverse it before you need a filling, or before it causes infection.

Check-ups and treatment for children are free on the NHS.

3. Limit sugar intake to mealtimes

It would be impossible to advise every patient to cut out all sugar completely, the issue occurs when sugar is consumed regularly, rather than as a treat.

So avoid grazing and sipping sugary drinks throughout the day, instead try to keep to mealtimes to avoid the length of time teeth are in the danger zone (acidic environment).

4. Keep sugar clear of night time

During the day, saliva helps wash away some of the sugary liquid from the teeth. It also contains minerals such as calcium and phosphates to help repair teeth. At night your saliva flow rate drops (ever woken up with a mouth as dry as sand? That’s why).

Saliva is your natural protection so anything left in your mouth during the night does a lot more damage.

So - nothing sugary before bed and nothing sugary during the night.

5. Infants should finish milk bottles before naptime

Milk contains natural sugars in the form of lactose, whilst lactose is good for you and not considered a free sugar, it can cause damage to teeth if left to sit in a child's mouth for a long time. ‘Baby bottle caries’ is incredibly upsetting to see, it can occur when the baby is put to bed with a bottle. At bed time the flow of saliva slows down and the baby swallows less often. This means the natural sugars in milk sit in contact with the teeth for hours on end, and can have irreversible consequences.

6. Supervise your children until 7 years of age

As a rule of thumb, until children can tie their own shoe-laces they do not have the dexterity to effectively brush their own teeth and hit every tooth surface.

So supervise toothbrushing, and encourage reaching those back teeth and avoiding a ‘quick scrub’.

The mouth is the gateway to our body, often our oral health can reflect the state of the rest of our body - so it is time to start prioritising it. We should all be aware that eating a varied, balanced diet will help tip the balance and promote the good bacteria. Following these steps can help guide us in the right direction and prevent any unwanted tooth trouble.

References

1. Pine C, Harris VR, Burnside G, Merrett MCE. An investigation of the relationship between untreated decayed teeth and sepsis in 5- year-old children. British Dent J. 2006;200:45–7.

2. Public Health England. 2020. Oral Health Survey Of 5-Year-Old Children 2019. [online] Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/oral-health-survey-of-5-year-old-children-2019> [Accessed 2021].

3. Grine FE. Enamel thickness of deciduous and permanent molars in modern Homo sapiens. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005 Jan;126(1):14-31. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10277. PMID: 15472923.

4. Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (2015) Carbohydrates and Health. http://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/445503/SACN_Carbohydrates_and_Health.pdf (accessed 2021).

5. Stephan R. M., Miller B. F. A quantitative method for evaluating physical and chemical agents which modify production of acids in bacterial plaques on human teeth. J Dent Res 1943;22:45–51.

6. Featherstone JD. Dental caries: a dynamic disease process. Aust Dent J. 2008 Sep;53(3):286-91. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2008.00064.x. PMID: 18782377.

7. Beals D, Ngo T, Feng Y, Cook D, Grau DG, Weber DA. Development and laboratory evaluation of a new toothbrush with a novel brush head design. Am J Dent. 2000;13:5A-13A.

8. Public Health England. Health Do, NHS England, BASCD, 2014. Delivering Better Oral Health: An Evidence-based toolkit for prevention. London. PHE